In April 2024, the General Department of Taxation (“GDT”) of Cambodia introduced its long-awaited Manual on the Methods and Procedures of Tax Audits, also referred to as the “Tax Audit SOPs.” This comprehensive document includes updated guidelines for tax audit procedures and aims to enhance the effectiveness and transparency of tax audits.

Currently, the GDT conducts approximately 4,000 tax audits annually, with some audits extending over multiple years due to their complexity. The introduction of the Tax Audit SOPs represents a significant step in the GDT’s efforts to reform and streamline tax audit procedures across the Kingdom.

In this article, we provide a clear and insightful analysis of the recently released Tax Audit SOPs. We will explore the key changes introduced, their practical implications for businesses, and what companies can expect moving forward.

Background: Rising Audit Activity Creates Pressure on Businesses

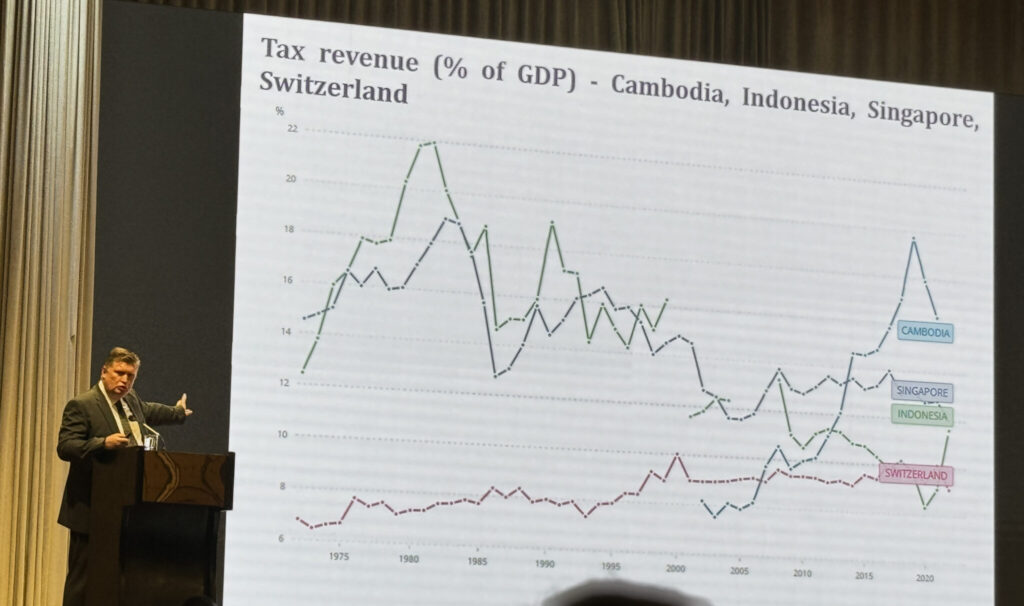

Before diving into the specifics of the new Tax Audit SOPs, it’s crucial to understand the evolving tax audit landscape through some pertinent statistics:

- Sharp increase in audits: Since 2018, the number of tax audits conducted by the Department of Large Taxpayers and the Department of Enterprise Audit has skyrocketed, rising from 907 to 3,883 in 2021, a staggering increase of 336%.

- Limited resources: While the number of audits has grown significantly, the number of tax auditors has only modestly increased, from 742 in 2018 to 746 in 2021. This highlights the growing pressure on existing resources.

- Focus on large taxpayers: Large taxpayers, estimated at about 4,000 and contributing 80% of the total tax collection, are a primary target of audits.

- Growing revenue from audits: In 2019, tax audit revenue contributed approximately 28% of the total tax collection, showcasing the significant role tax audits play in boosting government revenue.

- Limited success of appeals: Despite a growing number of tax audits, the appeal process remains largely ineffective. Annually, approximately 200 appeals are lodged with the Committee for Tax Arbitration under the Ministry of Economy and Finance, but only 50 of these cases are resolved. This low-resolution rate may discourage businesses from contesting tax reassessments.

These statistics paint a clear picture of the increasing challenges businesses are facing, with more frequent, less efficient tax audits, making the potential for a more streamlined and less time-consuming audit process welcome.

Key change #1: Gold Taxpayers Exempt from Routine Tax Audits

The new Tax Audit SOPs introduce a significant benefit for taxpayers with a gold taxpayer compliance certificate, exempting them from all tax audits while their certificate is valid, unless a risk or irregularity is detected.

This is a notable enhancement to the benefits of achieving gold taxpayer status. Previously, under Circular 007 MEF of 2017, gold taxpayers were subject to only one comprehensive audit every two years and were exempt from limited and desk audits, unless requested by the taxpayer.

A risk or irregularity refers to potential issues identified by the GDT before initiating an on-site audit. The GDT employs various methods to assess taxpayer risk and potential irregularities, which could include reviewing a company’s tax return filing history, economic activities, and accounting systems. According to the Tax Audit SOPs, risk indicators or irregularities include things such as frequent low tax payments, extended periods without tax payments, frequent changes or invalidations of invoices, significant year-to-year fluctuations in profit margins, discrepancies in financial statements, irregularities in debt affordability and repayment capacity, and deviations in profitability compared to similar businesses within the same industry.

While the Tax Audit SOPs provide a framework for identifying risks, how the exemption for gold taxpayers applies in practice may vary. Here’s why:

- Lack of specific guidance: The Tax Audit SOPs do not provide sufficiently detailed guidance on how the GDT assesses risk and determines the necessity for an audit on a gold taxpayer. This lack of clarity could lead to inconsistencies in application.

- Discretionary power: The SOP grants the GDT some level of discretion in initiating audits based on perceived risks. This could potentially lead to situations where compliant gold taxpayers face unexpected audits, creating uncertainty.

Despite these potential ambiguities, the new Tax Audit SOPs is a positive step towards a more streamlined and risk-based approach to tax audits in Cambodia. For businesses seeking to benefit from the gold taxpayer exemption, maintaining strong internal controls, accurate financial reporting, and a consistent tax filing history will be crucial in minimizing perceived risks by the GDT.

Other benefits of a gold tax compliance certificate

Achieving gold taxpayer status offers substantial advantages beyond exemption from routine tax audits. One key advantage is the streamlined Value Added Tax (“VAT”) refund process. According to Circular 007 MEF, gold taxpayers are entitled to receive VAT refunds for amounts of less than KHR500 million without undergoing a separate VAT audit. Additionally, gold taxpayers can apply in writing to be exempt from minimal tax payments.

Obtaining the two-year gold taxpayer compliance certificate involves submitting a written application to the GDT. The processing timeline typically ranges from one to two months.

Key Change #2: A Streamlined Desk Audit Process

Previously, desk audits could be lengthy and culminate in a Notice of Tax Reassessment (“NOTR”). The new Tax Audit SOPs introduce a significant change, transforming them into a more efficient and less time-consuming process focused on self-correction by taxpayers.

Steps in the new process

- First notice: The GDT initiates the process by issuing a letter outlining discrepancies found between the taxpayer’s information and their records. This is not a NOTR, but rather an opportunity for self-assessment.

- Taxpayers have 30 working days to correct identified issues and remit any additional tax owed. Crucially, any tax paid within this period is exempt from interest charges. However, the Tax Audit SOPs are silent on penalty exemptions. This implies that penalties may still apply to any unpaid tax, even if paid within the 30-day rectification period.

- If the taxpayer disagrees with the identified discrepancies, they can submit a written response to the GDT within the same 30-working-day window, explaining their position. The GDT will then review and respond within 30 working days, either accepting or rejecting the explanation. If rejected, the taxpayer has the right to formally appeal.

- Second notice: If the taxpayer fails to comply or resolve the issues within 30 working days of the first notice, a second notice is sent. The taxpayer must correct the issues and pay any additional tax within another 30 working days. Unlike the first notice, adjustments at this stage will include interest charges.

- Taxpayers can still object within working 30 working days, and the GDT will respond accordingly. A rejection of the taxpayer’s explanation can be formally appealed.

- Final step: on-site audit: Should the taxpayer remain non-compliant or the issues remain unresolved after 30 working days from the second notice, the process escalates to an on-site audit. This could evolve into a limited or comprehensive audit, depending on the findings.

While the new desk audit process aims to be faster by promoting taxpayers’ self-correction and reducing the need for lengthy audits, there are some potential drawbacks to consider. The tight 30-working-day window for responding to the first notice, while offering an opportunity to avoid interest charges, puts pressure on businesses to resolve discrepancies quickly. Additionally, the possibility for the process to escalate to a full audit after the first notice raises questions about its true efficiency in all cases.

Less New: Combined Audits – Avoiding Repetition

The Tax Audit SOPs address a common concern for taxpayers facing multiple tax audits, often with overlapping tax years. To streamline the process and avoid repetition, they allow the General Director of the GDT to authorize combined audits involving subordinate units.

What’s not new

This concept isn’t entirely new, as Article 8(4) of Prakas 270 MoEF.BrK (“Prakas 270”) already stipulates that: “In any special case, the General Director of the General Department of Taxation may allow a unit or multiple units to conduct a joint audit on the enterprise.” What constitutes a “special case” remains somewhat ambiguous, but the Tax Audit SOPs offer some clarity, suggesting that combined audits are intended to prevent repeated and overlapping tax audits.

Uncertainties remain

Key questions remain unanswered:

- Automatic vs. application-based: The specifics of when and how the GDT will combine audits remain unclear. It is not specified whether the process is initiated automatically by the GDT or if a taxpayer must submit an application.

- Potential for internal conflict: In practice, internal conflicts of interest between departments can arise. For example, in some cases, auditors conducting a limited audit might be motivated to issue an NOTR prematurely. This could be done strategically to keep the audit case within their department and avoid losing it to the team responsible for comprehensive audits. This raises a valid question: why conduct multiple overlapping audits when a single, comprehensive audit could address all potential issues?

Our experience with combined audits

In practice, taxpayers typically initiate combined audits by submitting written applications, which are often approved by lower-level GDT officials rather than requiring the General Director’s direct involvement.

Furthermore, combining audits doesn’t necessarily translate to a less comprehensive review. For instance, combining a limited audit with a comprehensive audit still results in a comprehensive audit, potentially involving auditors from various branches, like the DLT collaborating with the DEA.

In summary, while the concept of combining tax audits sounds appealing to streamline audits, the specific procedures and potential interdepartmental dynamics add layers of complexity that warrant careful consideration to apply for combining audits.

New Time Limits for Tax Audits, But Not That New

The Tax Audit SOPs introduce time limits for tax audits, but they are essentially an extension of existing regulations with some nuances.

Desk audits

The Tax Audit SOPs specify that desk audits must be completed within 12 months from the date the tax return is filed. For instance, if a taxpayer files their return on 31 March 2023, if a desk audit is initiated in September 2023, it must be completed by 31 March 2024.

On-site audits

The Tax Audit SOPs suggest a timeframe of one to six months for on-site audits (limited and comprehensive audit), with completion by the first quarter of the following year. This applies even if no irregularities or taxpayer errors are found during the audit.

For comparison, the Prakas 270, Article 9(7) established similar durations: three months for desk and limited audits, and six months for comprehensive audits.

Conditions and challenges

While these time limits seemingly offering a more predictable timeline, a closer look reveals a significant challenge: these deadlines hinge on the cooperation of the taxpayer to promptly provide “sufficient” documents and information. Unfortunately, neither the Tax Audit SOPs nor Prakas 270 defines what constitutes “sufficient” in this context.

This ambiguity creates a situation where audits can become open-ended. Without clear standards for evidence, the GDT could continually request additional documents, potentially extending the audit process well beyond the stated time limits. This lack of clarity has been a primary contributor to the protracted audit periods frequently endured by taxpayers.

Other New Aspects to Know

Beyond the streamlined desk audit process and exemption for gold taxpayers from routine audits, the Tax Audit SOPs introduce other significant changes.

Reduced documentation burden

The Tax Audit SOPs aim to reduce the documentation burden on taxpayers by stipulating that the audit department should utilize documents and information already provided during tax registration and filing, minimizing duplicate requests. However, the GDT retains the right to request additional documents if deemed necessary. Importantly, the Tax Audit SOPs mandate that the GDT maintain and share these additional documents with other relevant authorities to avoid future duplication.

Enhanced records and transparency

The Tax Audit SOPs emphasize the importance of recordkeeping and transparency during audits. Tax auditors are now required to document all verification of accounting records and taxpayer interviews. These records must be signed and stamped by the taxpayer or their representative. While this is likely already happening in many cases, the Tax Audit SOPs formalize the requirement, providing greater transparency for taxpayers.

Clarification of deadlines

The Tax Audit SOPs provide greater clarity on timelines. This applies to both GDT responses (e.g. decisions on taxpayer protests) and taxpayer responses (e.g. corrections and payments, written requests, protests). Previously stated deadlines of “60 days” are now clarified as “within 60 working days,” and “30 days” are clarified as “within 30 working days.” This distinction is important for taxpayers in accurately calculating response windows.

Conclusion

The new Tax Audit SOPs in Cambodia present both opportunities and challenges for businesses. The gold taxpayer exemption offers eligible businesses the advantage of avoiding routine audits. Additionally, all taxpayers can benefit from a streamlined desk audit process featuring a two-strike system, which allows businesses to promptly address discrepancies and potentially avoid interest charges. The Tax Audit SOPs also enhance clarity on deadlines and seek to reduce the documentation burden by utilizing information already provided during tax registration and filing.

However, uncertainties remain regarding the practical implementation of these reforms, particularly in terms of whether tax audits will indeed be streamlined and how the standards for “sufficient” documentation will be defined.

Navigating these reforms requires careful consideration and expert guidance. At Andersen in Cambodia, we specialize in helping businesses adapt to regulatory changes, optimize tax strategies, and ensure compliance with the latest legal requirements. Get in touch with us today to learn more.